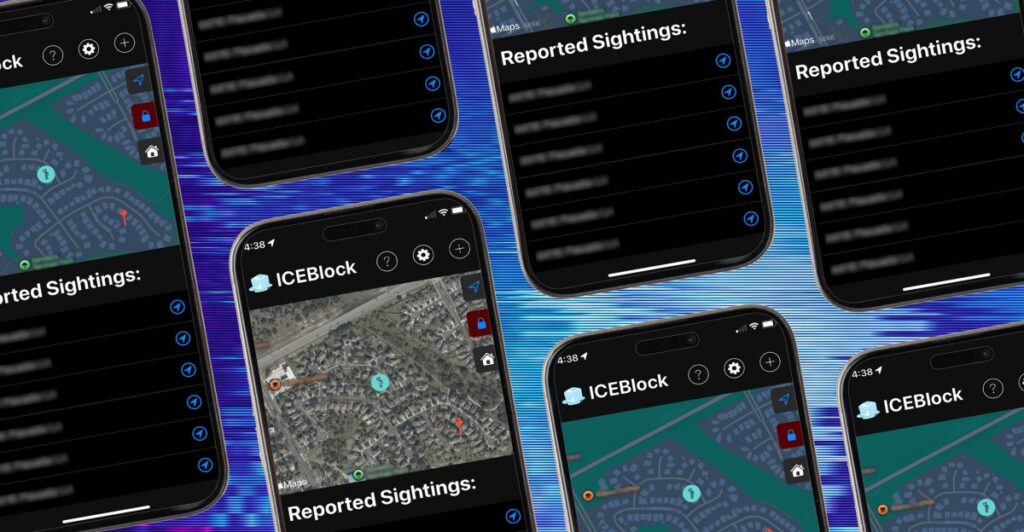

The developer of ICEBlock, an iOS app for anonymously reporting sightings of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials, promises that it “ensures user privacy by storing no personal data.” But that claim has come under scrutiny. ICEBlock creator Joshua Aaron has been accused of making false promises regarding user anonymity and privacy, being “misguided” about the privacy offered by iOS, and of being an Apple fanboy. The issue isn’t what ICEBlock stores. It’s about what it could accidentally reveal through its tight integration with iOS.

Aaron released ICEBlock in early April, and it rocketed to the top of the App Store earlier this month after US Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem called it an “obstruction of justice.” When calls for an Android version followed, however, the developer said it wasn’t possible. “Our application is designed to provide as much anonymity as possible without storing any user data or creating accounts,” reads part of the lengthy message. “Achieving this level of anonymity on Android is not feasible due to the inherent requirements of push notification services.”

The statement rankled some. The developers of GrapheneOS, an open-source, privacy-focused take on Android, took to BlueSky to accuse ICEBlock of “spreading misinformation about Android” by describing it as less private than iOS. The developers said that ICEBlock ignores data kept by Apple itself and claims it “provides complete anonymity when it doesn’t.”

Aaron told The Verge ICEBlock is built around a single database in iCloud. When a user taps on the map to report ICE sightings, the location data is added to that database, and users within five miles are automatically sent a push notification alerting them. Push notifications require developers to have some way of designating which devices receive them, and while Aaron declined to say precisely how the notifications function, he said alerts are sent through Apple’s system, not ICEBlock’s, letting him avoid keeping his own database of users or their devices. “We utilized iCloud in kind of a creative way,” Aaron said.

No security model is 100 percent safe, but in theory, ICEBlock has managed to limit the risks for people both reporting and receiving information. The Department of Homeland Security could demand information on who submitted a tip, but per Aaron’s explanation, the app wouldn’t have user accounts, device IDs, or IP addresses to hand over. Likewise, if ICE thinks someone used the app to find an operation and interfere, it could seek records from ICEBlock tied to who received a particular push notification — and again, it should come away empty-handed.

That trick is iOS-only, though. The ICEBlock iOS app can piggyback on Apple’s iCloud infrastructure to route push notifications because every iPhone user is guaranteed to have an iCloud account. Android users aren’t similarly required to create Google accounts, so “some kind of database has to be created in order to capture user information,” Aaron said. (Sharing reports across both phone platforms would create its own privacy challenges, too.)

I spoke to Gaël Duval, founder and CEO of /e/OS, another privacy-focused version of Android, and he admitted that Android’s push notifications require “a registration token that uniquely identifies a given app on a given device” and that this “would normally be saved on ICEBlock’s server.”

“It’s a long and random string,” he said, that doesn’t include either an Android ID or the IMEI that identifies a specific phone. “Google can still map it back to the hardware on their side, but for ICEBlock, it’s pseudonymous until you link it to anything else.” So, indeed, Android notifications would require ICEBlock to store potentially identifiable information. Normally, iOS would, too, but a clever workaround lets ICEBlock avoid just that.

But you might have spotted the problem: ICEBlock isn’t collecting device data on iOS, but only because similar data is stored with Apple instead.

Apple maintains a database of which devices and accounts have installed a given app, and Carlos Anso from GrapheneOS told me that it likely also tracks device registrations for push notifications. For either ICEBlock’s iOS app or a hypothetical Android app, law enforcement could demand information directly from the company, cutting ICEBlock out of the loop. Aaron told me that he has “no idea what Apple would store,” and it “has nothing to do with ICEBlock.”

For people who submit reports, Duval suggested that there might also be “a residual risk” from matching report timings and telemetry data, and Anso echoed a similar worry. But without the precise details of ICEBlock’s design — which Aaron is understandably reluctant to share — that’s impossible to verify. “Absolutely not,” Aaron said when I asked if it’s a concern. He insisted that “there is no risk” of Apple having data on which users have submitted reports.

Aaron said ICEBlock stores essentially no data on its users on iOS right now and that he couldn’t achieve the same setup on Android, a web app, or an open-source design. Critics argue he’s offering a false sense of security by offloading the risk to Apple. And while it’s not clear exactly what data Apple has on ICEBlock’s users, it’s enough to cast doubt on the claim that “there is no data.”

The question then is how safe that data is with Apple. Aaron insisted that “nothing that Apple has would harm the user,” and he was confident that Apple wouldn’t share it anyway. “Apple has a history, that when the government tries to come after them for things, they haven’t divulged that information, they’ve gone to court over it,” he said. “They’ve fought those battles and won.”

That isn’t entirely true. While Apple has engaged in some high-profile privacy fights with governments and law enforcement — including efforts to get into the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone or its recent refusal to build a backdoor into iCloud encryption in the UK — it complies with the majority of government requests it receives. In its most recent transparency report, for the first half of 2024, Apple said it agreed to 86 percent of US government requests for device-based data access, 90 percent for account-based access, and 28 percent for push notification logs. Many of these will be benign — they include help tracking lost or stolen phones, for example — but others relate to cases where an “Apple account may have been used unlawfully.” Demanding push notification data from both Apple and Google has become a key way for law enforcement to identify suspected criminals.

People have a constitutional right to record public police operations and share tips about sightings. As Aaron said, an app like ICEBlock — contrary to Noem’s claims — “is in no way illegal” under current American law. But during a period where neither the president nor the Supreme Court have much regard for constitutional rights, the question isn’t whether ICEBlock is legal, it’s whether any information that runs through it could expose people who resist ICE, legally or not.

“We don’t want anything,” Aaron said. “I don’t want a private database. I don’t want any kind of information on my side at all.”

And there’s the rub. ICEBlock says your data is safe because it doesn’t have any, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t out there. Do you have as much faith in Apple as Aaron does?

Read the full article here